On Sunday November 5th, I had the opportunity to travel to Bozeman, Montana, with two close friends to attend the last of Interior Secretary Deb Haaland’s Road to Healing events. The first Road to Healing event was held in Anadarko, Oklahoma, in July of last year. (Our colleague at NNCTC, Kimee Wind-Hummingbird, was in attendance.) Secretary Haaland and her team from the Interior Department have since held events in Michigan, South Dakota, Utah, Arizona, Washington, Minnesota, California, Alaska, and New Mexico.

Media outlets commonly refer to the series of events as the Road to Healing “tour,” but I am not comfortable thinking of them in that way. That term brings to mind tourism, and it risks trivializing what happens at the events: survivors of boarding schools share their testimony about what they endured, while Secretary Haaland and her staff listen on behalf of the federal government. These accounts are recorded and documented for posterity as part of a larger oral history project the Department has undertaken. The oral histories and the Road to Healing events, in turn, are part of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, which represents the first-ever comprehensive effort by the U.S. government to document and acknowledge the devastating effects of the boarding school policies it put in place beginning in the early 1800s and lasting through the 1970s.

Survivors have shared their stories about physical and sexual abuse; about violent suppression of traditional languages and cultural practices; about being separated from siblings and listening to other children crying in the night; and about how these sorrows have not faded with time and how some instances or objects such as lye soap serve as trauma reminders. As we know, these experiences continue to affect our communities across the generations. Traumas have been passed on from one generation to the next.

So while I don’t like calling these listening sessions a “tour,” I believe that the events are accurately named. The sharing of stories, though extremely painful, indeed has the potential to contribute to a road to healing. By entering survivors’ accounts in the federal record, the U.S. government offers a direct acknowledgement of its crimes against us—a necessary step.

My friends and I traveled to Bozeman because we wanted to be part of this journey. We took our seats in a ballroom on the Montana State University campus. The event began with the singing of an honor song. The President of MSU gave opening remarks and introduced Secretary Haaland who gave a short introduction to the Federal Boarding School Initiative, made some introductions of her staff, and talked about how her team’s primary function that day was to listen.

Secretary Haaland instructed survivors to state the dates and locations of boarding schools they attended when sharing their experiences, and although her staffers were clearly documenting what was said, Secretary Haaland listened with a notebook and pen in hand. I felt that this demonstrated her commitment to actively listening and documenting. I came prepared to listen, as well. I wanted to listen and support the elders who were there to share their own stories.

As the first survivor bravely shared their story of horrific abuses endured in boarding school, later life struggles with alcoholism, and eventual healing, allowing them to fulfil important cultural roles in the community, I began to understand the strength I needed—physically, mentally, spiritually, emotionally—to continue listening. I summoned my strength. It was the least I could do. It was nothing compared to what these elders had experienced firsthand. As survivors continued to share stories, some of them sharing on their own, some as groups, I began to recognize that people’s experiences were unique to the specific boarding schools they attended as well as to the years of their attendance. We so often think of the boarding school experience as one experience, rather than as many different experiences. That is no doubt partly because these stories have never been systematically collected before.

One common thread across specific locations and timelines was that many survivors recounted struggling in the aftermath of attending boarding schools before finding healing in later life, a crucial turning point which led to their becoming advocates for cultural revitalization and protectors of the subsequent generations of children in their communities. I wondered about those who had not lived long enough, or who had not been able to travel to one of these events, to tell their stories. What could we have learned about their experiences if they were here to tell us about them? We will never know. Likewise, we will never know the stories of those children who did not live to tell their stories, whose bodies were often buried on the grounds of their schools. It overwhelmed me to think how recent the experiences I was hearing about were. These were atrocities that continued to happen in our modern world, until not long before I was born, not in some distant historical time.

Even hearing the survivors’ stories, hearing them explain that they had overcome those unbearable experiences, I still could not fathom how they had done it. My thoughts kept cycling from the experiences that the survivors were recounting, back to my grandparents and their experiences, and then back to the present stories. Several times I thought how what might help the survivors in that moment as they were sharing would be if the rest of us could all somehow encircle them or somehow signal our physical support.

The story of one survivor in particular touched my heart because I knew her professionally. She had attended several NNCTC trainings over the years, trainings where we always talked about historical and intergenerational trauma. I wondered what she must have felt, sitting in those trainings and listening to people like me, who had not experienced these things firsthand, talk about these experiences that she knew intimately and had struggled to overcome. It made me think about the way we at the NNCTC, as well as the wider circle of professionals we interact with in the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, label and discuss historical trauma. I know that because of this testimony, I will be thinking about my work in a different way for the foreseeable future.

As that day’s session drew to a close, descendants of survivors and Indigenous leaders in state and Tribal governments spoke about potential legislation, advocated for support, and directly pressed the Department of the Interior about recent and continuing instances of injustice and harm over which they have presided. This part of the day’s dialogue coalesced into a shared wondering about what would happen now that the Road to Healing listening sessions were ending. Would the government be taking any actions in response to all of this? Would any changes occur?

In her closing remarks, Secretary Haaland shared her own family’s boarding school experiences and was emotional in thanking her staff for being so passionate and supportive in this initiative. She assured the audience that they would be utilizing what they have learned to take action. She did not provide any specifics, though.

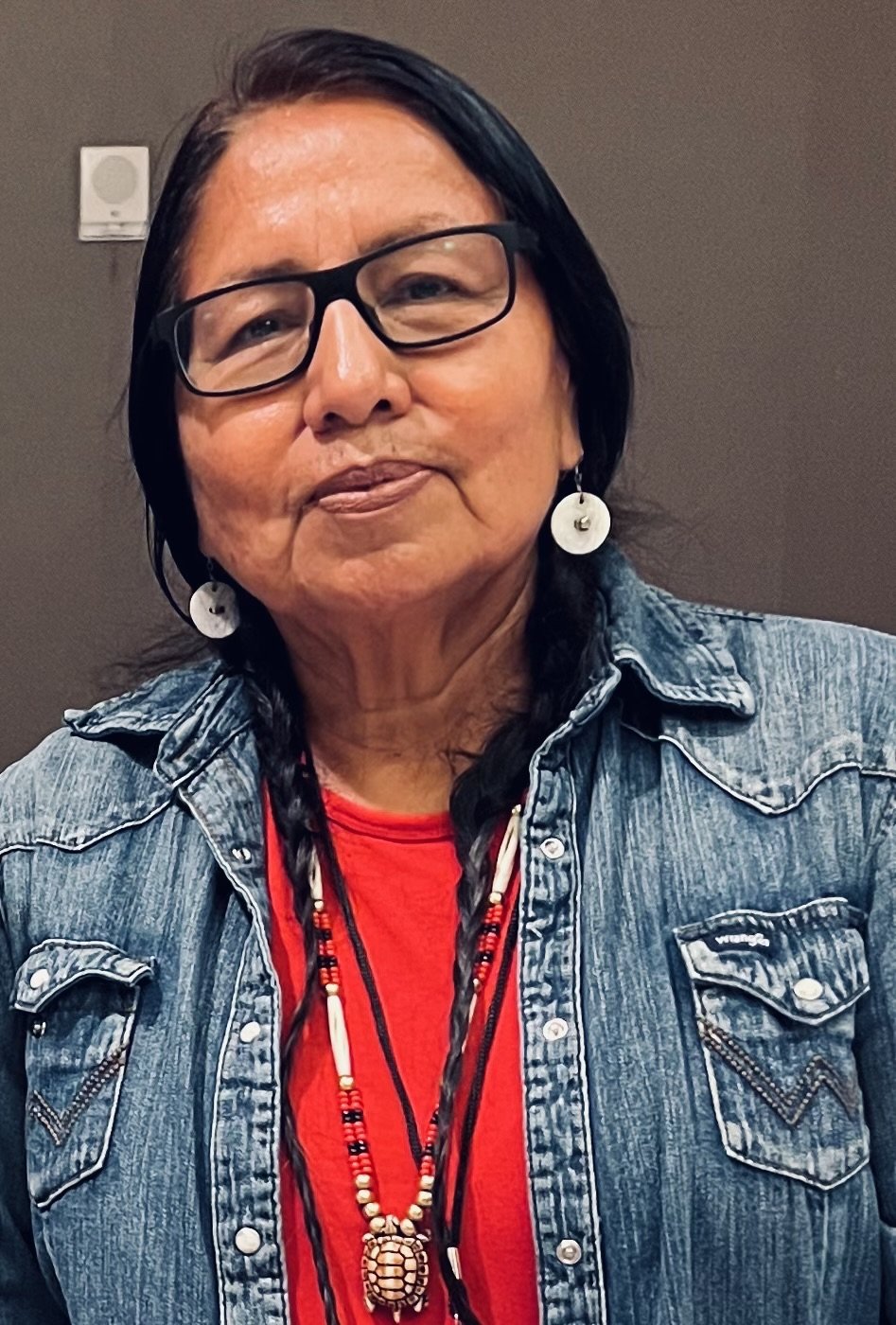

I only briefly interacted with Secretary Haaland, posing for a picture and making small talk. But between this interaction, the words she shared, and my observations of her during the event, I came away hopeful. I got the sense that she cared deeply and knew it was important as an Indigenous person to ensure that the Federal Boarding School Initiative will lead to further action. I also came away thankful that, at her urging, this opportunity to share and listen to survivors’ testimony had occurred.

In fact, it seemed a shame that these Road to Healing events were ending. Ideally, I thought, they would continue to occur at the community level, led by and on behalf of communities themselves, since each of our Tribal communities has its own stories about boarding schools and intergenerational trauma. At the same time, I recognized that the presence of a high-ranking representative of the federal government had provided an additional layer of validation for survivors who were sharing their stories, and it also created the possibility for systemic change. I thought about how it might be easier to maintain my hope that the government would in fact create positive change if representatives of other agencies had been there. Unfortunately, the Department of the Interior—the lone federal agency led by an Indigenous person—was the only one represented.

On the car ride home, my friends and I talked about all of those survivors we didn’t get to hear from, either because they had not lived long enough for this moment of reckoning or because they had not been able to make the trip. We wanted to hear more, in particular, about survivors of missionary boarding schools, a perspective that wasn’t represented during the event. We also talked about how despite knowing several of the survivors either socially or through our work, none of us had ever talked about their boarding school experiences with them before. And we talked about how the three of us in the car were close friends but had never talked about our own family members’ boarding school experiences.

As we began to share these stories now, processing our past silences and our current feelings, we began to grapple with the question of what each of us could do now to create positive change. I knew that the following day, I would be speaking to a group of counselors, supporting them as they attempted to address historical trauma in their counseling work. I am privileged to be able to do this work, but all three of us were wondering about something more. I was personally thinking about learning my own language and more about my culture and trying to understand what else I could do to pass this on to my daughter and the next generation.

The road to healing is long, my friends and I agreed, and it is not a straight line or a quick journey. We have to cope with our own continual risk of trauma, grief, and loss, experiences that may interrupt or slow our individual journeys. If many of us are simultaneously contending with similar disruptions, it may seem there is no road at all, and hope can be hard to find. We have to collectively remember that healing is not only possible but probable, and we have to remain mindful of the ways our families and communities have continually survived and found healing over the generations. Thankfully this journey is one we do not have to take alone.